Norway and Vikings – they simply belong together. But Norwegian history has a lot more to offer – it was an eventful journey to the country’s final independence in 1905. In our timeline you will find everything important that the proud country in the north has gone through.

Norway’s history is long and sometimes confusing – the path to today’s prosperous society was anything but easy. After early colonisation in the Stone Age, it was the Vikings who first and foremost shaped the country’s history – through trade, but also through bloody civil wars.

After Christianisation and its interim rise to great power status, however, the country fell into a crisis – its importance and power waned and Norway found itself in a series of unions – first in the Kalmar Union, then in a union with Denmark and then with Sweden – so at times Norwegian history is closely linked to the history of Denmark and Sweden.

With the new Norwegian Constitution, however, a new wind was blowing in Norway – and it was not far to official independence. After being occupied by Germany during the Second World War, Norway eventually developed into one of the richest and most advanced countries in the world. In our timeline, you can read more about how this came about and which historical events influenced the Scandinavian country and continue to shape it to this day.

From approx. 10,500 BC: Ice Age and Stone Age

Early Stone Age: First settlement in Norway

After the end of the last European ice age, the first people probably settled in what is now Norway around 10,500 BC. They came from the south and initially lived mainly in the southwest of the country, in the coastal regions and occasionally also in the north. As hunter-gatherers without a permanent home, they lived mainly from fish and meat.

From the rock carvings, which probably first began around 9000 BC, it can be assumed that the use of boats was already widespread at this time. The first tools were mainly made of flint.

Later Stone Age: Formation of society & first agriculture

The later Stone Age is roughly the period between 4000 and 1500 BC, when new population waves reached Norway. The battle-axe culture also brought the first agriculture to Norway, which was mainly practiced in the southern regions. Further north, people lived as semi-nomadic reindeer herders. The first social classes also emerged at this time.

1500-500 BC: Bronze Age

Sedentarization & tumuli

Even before the “official” beginning of the Bronze Age, the first objects were made of bronze, but they only became more widespread in the period from around 1500 BC among the rich chieftain families, who used bronze as a status symbol. The large burial mounds, which mainly date from this period, were also regarded as a status symbol.

The population of Norway became increasingly sedentary and lived in wooden longhouses, which led to the formation of larger social structures. In contrast to the Stone Age, the rock carvings from the Bronze Age no longer show scenes of hunting or farming, but presumably cultic and religious scenes in which the sun was the main focus.

500 BC - 800 AD: Antiquity and Iron Age

Roman Iron Age: trade connections to Europe

The Norwegian population seemed to have good trade relations with the Roman Empire around the turn of the millennium, for example, numerous Roman bronze cauldrons have been found, which were mainly used as urns – in addition to burial in the ground, cremation was also common at this time.

Another indication of the good relationship with Rome is the runic script, which first appeared in the 3rd century AD and was probably inspired by Roman and Greek characters.

First mention and cartographic mapping of Scandinavia

The first mention of the Scandinavian peninsula, called Scatinavia, as well as descriptions of local peoples and their kings were found in Latin writings from the years 79 and 98. Archaeological finds and records allow several sub-tribes to be distinguished, which were later combined into one empire.

Scandinavia was first mapped around the year 150 and appeared on Ptolemy’s world map.

5th century: Time of the migration of peoples

The increasingly brisk trade around the North Sea ensured that Norway and its chieftains continued to flourish. This can be seen above all in the lavish grave goods, such as weapons and objects made of gold. As the means of transportation, especially seafaring, improved, deeper connections between the chieftains also developed at this time, especially through marriages and the mutual education of sons.

550-800: Merovingian period

The last centuries before the rise of the Vikings were characterized by small kings who controlled individual villages or districts. The first political communities were likely to emerge, which meant that agriculture was resumed and iron production became more effective. The population also rose sharply. During this period, the language became Old Norse.

793-1066: Viking Age

793: Attack on the monastery of Lindisfarne

The rise of the Vikings and the Viking Age named after them began in the second half of the eighth century. The raid on the monastery on the English island of Lindisfarne in 793 is often cited as the official beginning. From 800 onwards, the number of raids on European coastal towns continued to increase. The most important sources of the Viking Age are the numerous sagas, which were written on the basis of oral traditions in the 12th and 13th centuries.

The reason for the new raids was probably the lack of arable land and improved ships and weapons, which made it quicker and easier for the Scandinavian seafarers to reach areas whose riches they could plunder and which often had no strong defenses. With the plundered and looted goods from the summer, survival in the fall and winter could be secured.

Clans and Thing

When the Vikings were not at sea, they lived together in clan communities. A chieftain stood at the head, while the other clan members determined their status within the hierarchy by their relationship to him. Although women were not equal to men, they could take over functions from them or go on voyages.

Although there were always feuds between different clans, individual groups increasingly joined together to form larger þing communities. The þing or thing was a popular assembly at which the chieftains, jarls and wealthiest peasants came together in the open air on a thing site and negotiated politics and laws. The four largest þings were the Gulathing around the Westfjords, the Frostathing around the Trondheim fjord, the Eidsivating in eastern Norway and the Borgating around the Oslo fjord.

New colonies in the North Atlantic

From the second half of the ninth century, many Norwegians embarked on a quest for freedom and independence. Due to a lack of land or displeasure with the powerful local rulers, large fleets were formed to undertake far-reaching military campaigns. Not only did they plunder, but some Vikings also settled there to establish their own settlements and territories.

The Vikings from Norway concentrated on the North Atlantic and settled in northern France, the British Isles, Iceland and Greenland – for example, the Irish capital Dublin was founded by Norwegians in the middle of the 9th century. In addition to the new trading centers outside Norway, cities were also founded within the country.

Harald Hårfagre: Norway’s first king

According to the sagas, Harald Hårfagre (Harald “Fairhair” – probably 850-933) conquered the island of Karmøy, whose ruler controlled the traffic along the Norwegian coast. From there, he expanded his probably already existing dominion in the southwest of the country and united the various dominions into one large one. After the Battle of Hafsrfjord, he proclaimed himself King of Norway – although for the time being he only controlled the western coastal area (“Vestlandet”).

After Harald’s death, fierce battles broke out among his descendants over the title of king and the rule of Norway – so it happened time and again that there were several kings at the same time.

11th-14th century: Norway in the Middle Ages

11th century: Christianization of Norway

The Viking Age in Norway ended with the introduction of Christianity. This was done by the three missionary kings Håkon I, Olav I Tryggvason and Olav II, who ruled Norway from the end of the ninth century until the middle of the tenth century and promoted Christianity. In addition to the kings, the trade and raids of the Vikings and Celtic slaves probably also had an influence on the spread of the new religion – Christianization was a long and laborious process.

The most “successful” of the missionary kings was Olav II, who was proclaimed a saint after his death and is therefore also known as “Olav the Saint”. Under him, who had been baptized in France in 1013, English clergymen came to Norway and the church in Norway was built up and expanded.

12th & 13th century: Norway in civil war

After the last Viking king Magnus Barfot died in 1103, Norway fell to his three sons. The middle son Sigurd took part in the First Crusade and was sole ruler after the deaths of his brothers. He named his illegitimate son Magnus as his heir, but shortly before Sigurd’s death, Harald Gille arrived from Ireland, claiming to be a son of Magnus Barfot as well. Sigurd legitimized Harald on the condition that he would not claim the throne during the lifetimes of Sigurd and his son.

Nevertheless, after Sigurd’s death in 1130, a dispute over the title of king broke out between Magnus and Harald, who was popular with the people, which was to continue into the next century. The bloody civil war continued even after the deaths of the first two candidates for the title of king, with Harald Gilles’ descendants now facing each other.

The last part of the “fratricidal wars” were the two so-called Bagler Wars between 1196 and 1208, in which the Baglers around Bishop Nikolas of Oslo and King Sverre, a grandson of Harald Gille, and his successor King Håkon Sverreson faced each other. Norway was initially divided into three parts, but after the deaths of the respective kings, Håkon Håkonsson, great-grandson of Harald Gille, was elected king.

1264-1349: Nordic superpower

Under Håkon IV (1204-1263), the kingdom experienced a “golden age” characterized by inner peace. In 1260, Håkon finally established the monarchy in the law of succession to the throne and also had blood feuds banned. In foreign policy, he strove to enlarge Norway; from 1262, for example, Iceland and Greenland officially belonged to Norway.

His son Magnus VI (1238-1280) carried out major legal reforms and introduced land law and town law, while the Hirðskrá law of allegiance was intended to introduce the courtly customs of the European continent – the Thing, for example, was replaced by royal courts. His successors Erik III and Håkon V continued to expand royal power in Norway. As a result, Norway experienced a period of prosperity in which new social groups developed alongside the simple peasants: the nobility, the clerics and the townspeople.

From 1340: Period of decline

After the death of Håkon V, his grandson Magnus VII became King of Norway in 1319. He was also a grandson of the Swedish King Magnus I and was also elected King of Sweden in the same year. Although Norway now appeared to be gaining power, the crown was losing more and more influence. After large parts of the population died in the plague of 1348/49, Norway not only lacked manpower and income, but the king also lost the support of the nobility.

As a result, Denmark gained more and more influence in Norway. Magnus’ son Håkon VI was married to the Danish princess Margaret, and their son Olav IV was elected King of Norway and Denmark, as Norway could no longer afford its own royal court. After Olav’s death in 1387, Margaret continued to reign alone and was elected Queen of Sweden in 1388.

1397-1523: Kalmar Union

1397: Negotiations in Kalmar

Margaret pursued the goal of uniting all three Nordic monarchies into one. To this end, she summoned representatives from Sweden, Denmark and Norway to a meeting in Kalmar.

There, a letter of union stipulated that the three countries should pursue a common foreign policy. The first king of the Kalmar Union was Erik of Pomerania, Margaret’s great-nephew and heir, who had already become King of Norway in 1389.

Norway in the Union

For Norway, the Kalmar Union meant a further loss of importance. Alongside Denmark and Sweden, between whom there were repeated disputes, Norway was unable to make its mark and became weaker and weaker. The country was still dominated by the consequences of the plague – there was hardly any population or revenue, the nobility became impoverished and Danish influence grew ever greater.

When the Swedish nobility successfully rebelled against the Danish crown under Gustav Vasa in the 1520s, causing the Kalmar Union to break up, powerless Norway fell to Denmark in 1523.

1523-1814: Union with Denmark

1536: The Reformation reaches Norway

In Norway, the Reformation took root somewhat later than in Denmark and Sweden – it was introduced by the Danish King Christian III, who had been in dispute with the Catholic Christian II over the Danish-Norwegian crown and wanted to consolidate his power in Norway as well.

This was the final blow to Norwegian self-government – the Norwegian church and its clergy lost all their power, and a period of Danishization began with the spread of the Bible in Danish. The Norwegian Imperial Council was also dissolved and the personal union between Norway and Denmark became more of a real union.

Norway within the Union

In the union with Denmark, Norway continued to exist as a separate kingdom and had its own laws and courts. However, the influence of Denmark was noticeable everywhere, for example also strengthened by the fact that another wave of plague decimated the Norwegian population and the nobility, which is why more and more Danes came to the fore.

There were innovations in the administration, among other things: with Akershus, Båhus, Bergenhus and Trondheim, there were four new “main fiefdoms”, which were initially administered by Danish officials, but later (after the Northern Seven Years’ War 1563-1570) by Norwegians themselves. The official language was Danish.

17th century: Tensions with Sweden

In terms of foreign policy, Denmark-Norway was primarily in conflict with Sweden at this time. There were repeated wars between the neighboring countries. Denmark was initially able to maintain its supremacy, but in the 17th century the tide turned in Sweden’s favor and the country rose to become a great power in Europe.

In the course of the Thirty Years’ War, Denmark lost large parts of its territory to Sweden, including parts of Norway, even though it regained territories in the Peace of Copenhagen. Nevertheless, there was a constant fear of a Swedish invasion of Norway, which is why attempts were made to give the Norwegians a sense of equality in the Union – but in fact Norway remained in second place.

The Great Northern War from 1700 to 1721 put an end to Sweden’s supremacy. Denmark-Norway fought alongside the new superpower Russia, but did not gain any territories itself. Instead, a policy of neutrality was adopted.

The Napoleonic Wars and the end of the union with Denmark

Denmark-Norway first became involved in the Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815) in 1801, but only really became active in 1807, when Great Britain secured the Danish-Norwegian navy in the course of the bombardment of Copenhagen. The loss of the ships not only meant the loss of protection, but also trade opportunities. Denmark-Norway abandoned its policy of neutrality and instead entered into an alliance with France – although the latter’s blockade of Great Britain caused great damage.

Norway fell into isolation and was plagued by economic crises and famine. This led to an increasing desire for independence and autonomy in Norway.

Meanwhile, Sweden was in an alliance with Russia, and from 1813 to 1814 there was a direct war between Denmark and Sweden, which Sweden won. In the subsequent Peace of Kiel, which was concluded on January 14, 1814, Denmark ceded Norway to Sweden.

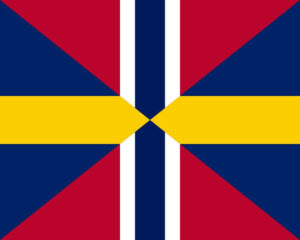

1814-1905: Union with Sweden

1814: Brief independence

Although Denmark and Sweden had agreed on the future fate of Norway in the Peace of Kiel, Norway itself was not very enthusiastic. The Danish crown prince (and later king) Christian Frederik joined the Norwegian independence movement, adopted the Norwegian constitution, which is still in force today, at a meeting on May 17 and crowned himself King of Norway.

Although May 17 is still the Norwegian national holiday today, Norway only remained independent for a short time. Sweden did not accept the new independence and launched an attack, whereupon Christian Frederik resigned after only two months in office.

This conflict ended with the Moss Conventions and Norway agreed to enter into a personal union with Sweden as an equal partner: although the Swedish king would in future be head of state and a common foreign policy would be pursued, Norway’s parliament and constitution would remain in place. The union was officially established on November 4.

The Norwegian Constitution

Although the Norwegian Constitution was slightly modified when the Union was founded, it remained the same in general. It was strongly influenced by the American and French constitutions and therefore focused primarily on freedom, but also remained true to Norwegian legal traditions. With the constitution, the Norwegian parliament became the most powerful parliament in Europe and Norway became a constitutional monarchy in which parliament had the say.

As a result, there were repeated tensions between the Norwegian parliament and the Swedish kings, as both sides demanded more power for themselves. In 1884, the Swedish King Oskar II agreed to parliamentarism and appointed the liberal politician Johan Sverdrup as Norway’s first prime minister.

Norway in the personal union

Norway was a largely equal partner, but things were still simmering. Especially in domestic policy, for example in the area of finance, it took Norway a long time to get back on its feet. There were major supply problems in the rural regions in particular, which led to a large wave of emigration to the USA in the 19th century.

In the second half of the 19th century, however, there was an economic upturn, mainly due to maritime trade – at the end of the 19th century, Norway had the third largest merchant fleet in the world after Great Britain and the USA. As trade flourished, industrialization also spread, which in turn promoted trade.

After the nobility was abolished in 1821, it was mainly rich merchants, farmers and civil servants who were now at the top of society – at the same time as industrialization, the labour movement also emerged, which was to have a major influence on the country in the years that followed.

A Norwegian national feeling

At the beginning of the union, Norway was financially at rock bottom, but the new independence nevertheless provided a boost, particularly in Norwegian culture. The creation of a “Norwegian” identity began, Norwegian artists, writers and musicians were strongly promoted and national romanticism was very popular.

In addition, a new written language was developed – Nynorsk (“New Norwegian”) was based primarily on rural dialects, while the existing Norwegian (today’s Bokmål) had developed from the Danish language.

With this flourishing new culture and extensive political independence, national consciousness and the desire for complete independence grew more and more. Folklore, history, sport and polar research also played their part in this movement, but it was the Norwegian farmers who supported it the most.

20th & 21st century: The Norwegian Nation State

1905: Norway becomes independent

Between 1902 and 1904, final tensions and negotiations arose between the Norwegian parliament and the Swedish crown over the consular system. When the Swedish King Oskar II refused to allow the Norwegians an independent consular system, the Norwegian government resigned in 1905, as a result of which Parliament declared the King incapable of trading and the Union a failure.

On August 13, 1905, a referendum was held on the dissolution of the Union, which was confirmed by 99.5%. With the Treaty of Karlstad on August 23, the borders were established and Norway officially became a constitutional monarchy. The new king was the Danish Prince Carl, who himself called for a referendum before being crowned Haakon VII on November 18.

After the Radicals won the election in 1906, there were a number of changes to voting rights – Norway was the fourth country in the world to introduce women’s suffrage in 1913 – only Finland was faster in Europe.

Norway in the First World War

After independence, Norway’s economic upturn continued for the time being – but the Nordic country was also affected by the European crises. Although Norway was officially neutral during the First World War and largely stayed out of the war, it was still involved in the conflict through its merchant fleet and was heavily influenced by the Axis powers.

For example, trade with Germany was stopped. As a result, German submarines repeatedly sank Norwegian merchant ships, which increased the mood against Germany. In addition, Norwegian waters were mined by the British with the government’s permission. Officially, however, Norway maintained its neutrality.

Interwar period

After the end of the war, there was initially a brief economic upturn, but this soon subsided – the reason for this was the prohibition that had been in force in Norway since 1914. From 1927, however, things started to pick up again, before the Great Depression and subsequent Great Depression led to high unemployment.

Nevertheless, Norwegian politics had also changed dramatically, as the Russian Revolution had shaken the international labor movement to its core – including in Norway. At the same time, the split between left and right was driven forward, especially after the Great Depression of 1929, when both camps became increasingly radicalized. Political stability did not return to Norway until 1935.

In terms of foreign policy, Norway was awarded the entire territory of Svalbard in 1925; an attempt to take over parts of Greenland failed at the International Court of Justice. Otherwise, Norway increased its cooperation in international organizations and joined the League of Nations in 1920, for example.

Second World War: Norway under German occupation

After the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, Norway declared its renewed neutrality early on. However, this did not prevent the German Wehrmacht from invading and occupying the country from April 1940 as part of “Operation Weserübung” – Norway’s surrender took place just two months later, on June 10. The Norwegian royal family and the government had already fled to Great Britain a few days earlier and encouraged the resistance of the Norwegian population from exile.

As the German occupiers feared an Allied invasion at any time, a large number of German soldiers were stationed in Norway at all times. In addition, numerous defenses were built along the coast and the Atlantic Wall was strengthened.

For all appearances, Norway was able to maintain its autonomy under German occupation, as the real plan was to win over the Norwegians as allies – but this failed resoundingly. As the collaborationist government was not recognized, the German occupation policy eventually became increasingly harsh.

This also increased the resistance of the Norwegian population, who were already suffering from war, poverty and famine. They divided themselves into the home front and the foreign front. Resistance fighters blew up hydroelectric power stations and sank German cargo ships, for example.

From the end of 1944, the Wehrmacht withdrew from northern Norway due to the advancing Red Army. They pursued a scorched earth policy – local residents were deported and everything left behind was destroyed and burned.

After the German capitulation in May 1945 and the end of the war in Europe, King Haakon returned to Norwegian soil on June 7, 1945, exactly five years after his escape, thus officially sealing the end of the occupation.

After the Second World War

After the end of the war, the biggest tasks were reconstruction and coming to terms with the crimes of the previous years. Almost 50,000 people were prosecuted for treason. In addition, the Norwegian state confiscated German capital and thus achieved supremacy in the production of raw materials, for example.

Politically, the Social Democrat Einar Gerhardsen came to the fore in the post-war years, serving as Prime Minister from 1945 to 1965 and forming a wide variety of governments. He followed the Swedish model and ensured economic and social upturn. He was also instrumental in Norway abandoning its policy of neutrality and becoming a founding member of NATO in 1949. This also enabled Norway to participate in the Marshall Plan.

Scandinavian and Nordic cooperation began in the 1950s, for example within the framework of a passport union and a common labor market. The Nordic Council has also existed since 1952. In the European area, Norway became part of EFTA in 1960 – but membership of the EEC was rejected.

The path to today’s affluent society

Since the discovery of oil and gas in the North Sea in the 1970s, Norway has been considered one of the richest countries in Europe. With the newly acquired wealth, a modern society with a high standard of living has developed.

Membership of the European Community or Union is still rejected, but Norway has been part of the European Economic Area since 1994 and a member of the Schengen area since 2001.

Since the 1980s, Norway has been politically shaped above all by Gro Harlem Brundtland, who became the first female Norwegian Prime Minister in 1981 and also held this post between 1986 and 1996, as well as Kjell Magne Bondevik (Prime Minister 1997-2000 & 2001-2005) and Jens Stoltenberg (Prime Minister 2000-2001 & 2005-2013, first Norwegian NATO Secretary General since 2014).