Although Iceland has a comparatively short history compared to other European countries, it has a lot to offer – the island state with breathtaking nature has the second oldest existing parliament in the world and produced great seafarers, but the road to independence was long and difficult. Here you can read about the most important events in Iceland’s 1150-year history!

Iceland was the last European country to be populated due to its remote location – although myths and legends surround a fabled island in the Arctic Ocean, it was not permanently settled until 874, when Norwegian Vikings came across the island in search of new land.

Initially a free state with the Althingi, the second oldest parliament in the world, and legendary sailors and warriors, Iceland first came under Norwegian and then Danish rule – Iceland’s history is closely interwoven with the other Scandinavian countries, especially Norway and Denmark, and it was a long road to independence.

Iceland was part of various Scandinavian unions and flourished above all in the fishing industry. After the First World War, the Kingdom of Iceland was finally created with the aim of full independence – this was achieved during the Second World War in 1944. Although conflicts such as the Cod Wars threatened peace in Iceland at times, the country developed rapidly into the modern industrialised state we know today – even though the financial crisis of 2008 is still being felt.

From ca. 4th century BC: discovery and earliest settlement

The myth of Thule

It is not known exactly when Iceland was discovered and set foot on for the first time. However, it can be assumed that from the 4th century BC onwards, sailors repeatedly stopped on the island, for example the Greek Pytheas of Masilia, who started the myth of the island of Thule with his writings.

Pliny the Elder and the monks Beda and Dicuilus also wrote about the legendary island. It is unclear whether Thule is really Iceland, but there are clues and similarities.

874-930: Land occupation period

874: The first permanent settler reaches Iceland

Although seafarers came to Iceland time and again before that, the official and permanent settlement of the island began in the last third of the 9th century. The first settler was the Norwegian Ingólfur Arnarson, who settled in the region that is now Reykjavík. His example was followed by around 400 other families who divided the land among themselves. The population consisted mainly of Norwegian Vikings, who were looking for new colonies in the North Atlantic, and their Celtic slaves.

The Landnámabók

The Landnámabók is an old Icelandic text and an important historical source for the settlement of the islands. It is a list of names of the 400 settlers who settled on Iceland between 870 and 930.

However, the Landnámabók was not established until the 11th century, which is why the descendants of the first settlers are also mentioned.

930-1262: The Icelandic Free State

930: Creation of the Althingi

The first Icelanders originally came from Norway and were therefore very familiar with thing assemblies. These initially only took place regionally in Iceland until the Althingi was founded in 930 – and with it the Icelandic state system or the Icelandic Free State.

It was one of the earliest parliaments in the world, where Icelanders met for two weeks in the summer and discussed law and politics in the open. The site of the Althingi was Thingvellir (Assembly Plain) near Reykjavík.

Voyages of discovery during the saga period

The period between 930 and 1030 is also known as the saga period, as this is when most of the Icelandic sagas written in the 13th century were set. In addition to conflicts and events in Iceland itself, the sagas are also about explorers – some great names were born in Iceland, above all Erik the Red, the discoverer of Greenland, and his son Leif Eriksson, the first European to set foot on the American mainland.

Although most of the early settlers were pagans, they also came into contact with other religions on their Viking voyages, first and foremost Christianity. The Icelanders were also influenced by the Christian Celts. From around 980, a Christian mission started from Hamburg. After the Icelanders initially rejected the new religion, it was officially introduced at the Allthing in the year 1000. All Icelanders thus became Christians, but pagan customs were initially allowed to continue in secret.

While Christianization in Scandinavia initially suffered some setbacks, Christianity was slowly but surely able to establish itself in Iceland. The Norwegian King Olav III was one of the greatest supporters of Christian Iceland, sending wood for churches to Iceland and ensuring that the legal exemptions for pagans were withdrawn. In addition to churches, schools and monasteries were also built. The first Icelandic bishop was Ísleifur Gissurarson.

1030-1180: Time of Peace

The eleventh century was largely peaceful and did not see much conflict. There was enough room for everyone, which is why power was evenly distributed among the individual chieftains and rulers. In addition, the country was largely stabilized both politically with the Allthing and religiously with Christianity.

The first conflicts arose in the 12th century, which subsequently increased and put an end to the peaceful period.

1180-1262: Sturlungen period

The late 12th and 13th centuries were characterized by bloody conflicts and gender feuds. The Norwegian king Håkon IV wanted to bring Iceland back under his direct control and encouraged conflicts between Icelanders.

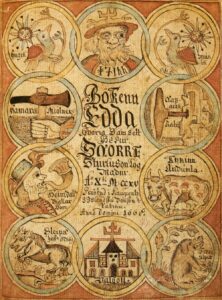

Snorri Sturluson, who was a courtier in the Norwegian royal house and, as a successful politician of the powerful Sturlungen dynasty, had actually sworn to bring Iceland back under the king’s power, played a formative role in this period. However, he broke his promise and is today best known for his works, especially the Snorra Edda. The other world-famous Icelandic sagas were also written in the 13th century.

1262-1380: Under Norwegian rule

The Old Treaty

With the Old Treaty of 1262-1264, King Håkon finally officially became King of Iceland after most of the Icelandic chieftains had sworn allegiance to him and Norway had threatened Iceland with a trade boycott. With the treaty, the Icelanders recognized Håkon as their ruler and became taxpayers, although these taxes were capped. The king also assured the Icelanders of peace and the retention of the Allthing.

When Håkon’s son Magnus seized power, he ensured that the Jónsbók code of law was drawn up for Iceland, which was adopted by the Allthing in 1281 and significantly increased Norwegian influence. The Allthing was then quickly disempowered and the Norwegians also intervened heavily in Icelandic administration and politics.

14th century: Century of catastrophes

The 14th century was a century of terror for Iceland. Not only did the Norwegians, who had been in a union with Sweden since 1319, initially largely determine what happened in the country, but the island was also plagued by a series of armed conflicts and disasters.

In 1341, the volcano Hekla erupted, causing abandoned farms, failed harvests and famine. As in the rest of Europe, Iceland was also affected by epidemics, albeit later and to a lesser extent due to its remote location – the plague, for example, probably only reached Iceland during its second wave between 1402 and 1404, but then it was devastating.

1355-1374: Royal union between Sweden and Iceland

The period of decline in Norway meant that Norway lost more and more power. The country was particularly hard hit by the plague, and the Norwegians were dissatisfied with the Swedish-Norwegian King Magnus VII and elected his son Håkon VI as independent Norwegian king.

However, after Håkon’s coronation, Magnus retained power over the Atlantic provinces – including Iceland. After the death of Magnus, who had lost his Swedish royal title to Albrecht of Mecklenburg in 1364, Iceland was returned to Norway.

1380-1944: Under Danish rule

Union between Norway and Denmark

While Norway lost more and more power, the rise of Denmark took place. When King Håkon VI of Norway died, his underage son, who was already King of Denmark, also became King of Norway as Olav IV in 1380. This created a union between Norway and Denmark; Iceland paid homage to the Danish king in 1383, but continued to belong to Norway for tax purposes.

1397-1523: Iceland in the Kalmar Union

After Olav’s death, his mother and regent Margrethe took over the rule of the Scandinavian lands. With the Kalmar Union, she united the countries under a single king. All countries retained their own legislation and foreign policy was to be conducted jointly.

Iceland was not heavily involved in the union due to its distance and did not really get involved on its own initiative. Sweden broke with Denmark for the first time in 1448 and effectively left the Kalmar Union, the official end followed in 1523 with the rise of Gustav Vasa. The union between Denmark and Norway remained, to which Iceland also continued to belong.

Trade with the rest of Europe

After Norway lost its trade monopoly with Iceland, Icelandic trade relations with the rest of Europe flourished. Trade with England, Denmark and the German Hanseatic League in particular increased. This rise was mainly due to the fact that the Icelanders quickly specialized in (dry) fish – with a growing population on the European mainland, more food was needed. Other exports included wool and tran.

However, the growing trade did not only have positive consequences for the Icelanders – goods became scarcer and more expensive. In addition, the unknown disease that triggered the devastating Great Plague of 1402-1404 arrived in Iceland on a merchant ship.

1536-1550: Reformation in Iceland

Under King Christian III, the Protestant-Lutheran denomination was officially introduced in Denmark, Norway and the Faroe Islands in 1536. Iceland was also supposed to convert to the new faith, but the Catholic bishops refused. However, Lutheran services were already being held in Hafnarfjörður at this time.

This led to a violent conflict between Protestants and Catholics. The first Lutheran bishop in Iceland was Gissur Einarsson in 1540, who continued to spread Protestantism. The Catholic bishop Jón Arason rebelled against this and became very powerful, especially after Gissur’s death. It was not until his imprisonment and execution in 1550 that the Reformation was finally established in Iceland.

17th & 18th century: Iceland in the early modern period

The successful Reformation further strengthened the power of the Danish king. From 1602 to 1787, Denmark held the trade monopoly, and in 1662, the Danish King Frederick III introduced absolutism in his kingdom – in Iceland, the Althingi was further disempowered until it was finally abolished in 1800. The church also lost some of its power during the Enlightenment.

After difficult economic years with cold temperatures and famine, the climate changed for the better in the 18th century. Most Icelanders were still active as farmers and fishermen and stimulated the local economy. The second half of the 18th century saw a number of reforms and innovations, but these were curtailed by a series of volcanic eruptions and cold spells.

19th century: First aspirations for independence

After the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark ceded Norway to Sweden. Although Iceland had only become part of the Danish-Norwegian Union because it belonged to Norway, the country continued to belong to Denmark.

Many Icelanders studied in Copenhagen, where they came into contact with the ideas of nationalism. These were also well received at home in Iceland, especially in connection with political independence. Literature and culture also flourished in the wake of national romanticism. At this time, Reykjavík also emerged as the political and intellectual center of Iceland.

In 1843, the Althing was reintroduced in Reykjavík, although the parliament only had an advisory function. When the constitutional monarchy was introduced in Denmark in 1848, Iceland remained part of the empire. At least Iceland was given its own legislature in 1874.

1918: Kingdom of Iceland in the real union with Denmark

At the beginning of the 20th century, Iceland experienced a strong upswing in many areas, for example the first Icelandic university was founded in 1911. There were far-reaching changes in politics, an Icelandic minister was appointed to the Danish government in 1904 and women’s suffrage was introduced in 1915. During the First World War, Iceland, like Denmark, maintained its neutrality, but was affected by trade shortages and inflation.

After the end of the war in 1918, there were changes in the European order, from which Iceland also benefited. Following a referendum, Iceland became an independent kingdom in a real union with Denmark, with King Christian X as head of state. The Icelandic flag was also officially introduced. The treaty was to remain in force for 25 years, after which a referendum on complete independence was planned.

1939-1945: Iceland in the Second World War

Four years before the end of the Treaty of Union, the Second World War broke out. Denmark and Norway were occupied by Germany in April 1940, but Iceland remained neutral and rejected a military alliance with Great Britain. As a result, Iceland was occupied by British forces in May 1940 in order to forestall a possible German occupation. However, this took place peacefully and without violence.

Iceland was expanded and became an important base for the Allies in the Atlantic. In 1941, the USA took over the military protection of Iceland. At this time, both countries were still neutral. This period was also peaceful, with the exception of a few conflicts.

Since 1944: Independent Republic of Iceland

1944: Iceland finally becomes independent

With the occupation of Denmark, the Union was already effectively dissolved anyway and it had already become clear before the war that the treaty with Denmark would not be renewed. With the agreement of the Americans, the Icelandic government decided to let the three-year period stipulated in the treaty expire and then establish a republic. Denmark was still occupied and could not object.

From May 20 to 23, 1944, a referendum was held on the dissolution of the Real Union and the constitution of the Icelandic Republic. 97.35% voted for the dissolution and 95.04% for the establishment of the Republic. On June 17, 1944, Iceland was officially declared independent at the historic site of Thingvellir, and Sveinn Björnsson became the first president.

The path to the modern industrial state

After the end of the Second World War, Iceland quickly joined various alliances, including the United Nations (1946), NATO (1949), the Council of Europe (1949) and the Nordic Council (1952). The military alliances in particular are of great importance to the country, as it does not officially have a military itself. A US military base was operated from 1951 to 2006.

Iceland became a member of the European Free Trade Association in 1970. Even though EU membership was rejected, Iceland established good relations with its European partners and became part of the European Economic Area in 1994. Overall, the country developed in the middle of the twentieth century into the modern and socially industrialized country it is known as today.

Iceland was also able to establish itself culturally on the world stage: in 1955, the author Halldór Laxness was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. The Hallgrímskirkja, the country’s second largest building and Reykjavík’s landmark, was built between 1945 and 1986.

1958-1976: The cod wars with Great Britain

Since the 1950s, there have been repeated discussions and conflicts about the fishing zones and rights, as well as the territory of Iceland. The expansion of these zones by Iceland in 1958, 1972 and 1975 displeased the United Kingdom in particular, which led to the three so-called Cod Wars, in which the Icelanders were able to assert their interests.

In the first Cod War from 1958 to 1961, there were relatively harmless clashes between the Icelandic coastguard and British warships until Iceland complained to the UN and the NATO Council recalled the UK. During the second cod war in 1972/73, the only casualty of the wars occurred, albeit without violent involvement. The USA ensured that the conflict was settled.

During the third Cod War in 1975/76, Iceland broke off diplomatic relations with the British, but this conflict was also settled by negotiation.

2008-2011: Iceland’s financial crisis

The global financial crisis from 2007 onwards hit Iceland particularly hard. The three major Icelandic banks had become heavily indebted and collapsed, and the head of the Icelandic central bank was also involved in the banks’ activities. In mid-2008, Iceland’s foreign debt stood at around 50 billion euros.

As a result of the crisis, the exchange rate of the Icelandic krona fell enormously and various Icelandic companies had to file for bankruptcy, causing the unemployment rate to rise sharply. In addition, many politicians and members of government resigned. Membership of the EU and eurozone, which had previously been rejected, also came back into discussion. An application for membership was even submitted in 2009, although this was withdrawn in 2015.

After the countermeasures from 2011 led to positive GDP growth and the international bailout expired on August 31, 2011, the Icelandic financial crisis was declared over on the same day. Boosted tourism and the cultural industry (especially books) also provided an upswing. However, the financial crisis is still omnipresent for many Icelanders.